Toronto

Toronto is home to an extensive, 48 mile long subway network, consisting of four lines that serve 75 stations. The region is currently in the process of constructing two new light rail lines that will expand the system by 31 mile and 39 new stations.

Project delivery dynamics in the region are characterized by significant political interference and a fraught governance structure. Amid rising costs on major projects, some researchers have raised questions about the depth of subway stations and tunnels. In addition, rising construction costs have compelled the region to utilize public-private partnerships, with mixed results. The provincial (statewide) government has also recently taken steps aimed at cutting timelines on major projects, most notably by creating a separate, expedited environmental review process for transit and giving public entities considerably more power over utility relocation, property acquisition, and ability to utilize municipally-owned ROW.

Table of Contents

Governance Overview

In metropolitan Toronto, transit planning, delivery, operations, construction, and finance are largely handed at the provincial level. Per the Canadian constitution, responsibility for intra-province transportation is delegated to the provinces, while the national government primarily oversees international and inter-province transportation services.

The provincial government has been the primary funder of rapid-transit infrastructure since the 1970s, though the federal government has become increasingly involved in transit in recent years. Amid cost overruns on the Toronto-York-Spadina subway extension (TYSSE), the province has taken over rapid-transit planning, project delivery and construction, which were traditionally handled by municipalities. The Toronto Transit Commission operations, which had received a provincial subsidy for about a quarter century beginning in the early 1970s, are city responsibilities in full.

Most recent projects are funded using provincial and local funds, though the national government contributed just under 19 percent ($579 million) to the TYSSE subway project through the Build Canada Fund, and 13 percent ($275 million) to the Finch West Light Rail project.519 Nationally, the Build Canada Fund provided $7.2 billion towards individual infrastructure projects (contributing between 25 to 50 percent of project costs) between 2007 and 2014 and the national government is becoming increasingly more involved in the funding of major projects through programs like the Investing in Canada Infrastructure Program, in which the Canada Infrastructure Bank has committed nearly $17 billion to transit.520 In May 2021, the federal government announced it would provide nearly $10 billion in funding—amounting to 40 percent of project costs—for the next wave of major transit projects in Toronto: the Ontario Line, Scarborough Rapid Transit replacement, Eglinton Crosstown light rail line, and the Yonge-North subway extension.521

Metrolinx is a provincial agency that serves as the regional transportation authority for the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA).522 It was created by the province of Ontario in 2006 to design the region’s first-ever transportation plan. That plan—dubbed the Big Move—was released 2008 and set out a new $42 billion transportation program and series of major investments for the region.523 In 2009, Metrolinx was merged with GO Transit, Ontario’s regional transit system. GO Transit functions as an operational division of Metrolinx, but only operates commuter trains and commuter buses.

In 2018, the mandate of Metrolinx was amended to give it authority over transit planning, rather than wholly focusing on transportation planning. Responsibility for regional transportation planning was transferred to the Ontario Ministry of Transportation.524 Today, Metrolinx has sole responsibility planning and implementing the numerous major transit expansion projects and initiatives in the region, along with other responsibilities like developing a common regional fare system. Metrolinx is governed by a board of up to 15 citizen members who must be recommended by the Ontario Minister of Transportation and approved by the Province. Prior to 2009, the board was largely made up of mayors and other elected officials from the region. After the merger of Metrolinx and GO Transit, the board’s structure changed, and elected officials were removed.

The Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) is the exclusive local public transit operator for the city, and accounts for the about 85 percent of all public transit trips in the region. It is governed by a 10-person board, appointed by the Toronto City Council (four are public members and six are City Councilors). The TTC was the lead agency responsible for project delivery until 2015, when control was transferred to Metrolinx amid cost overruns on the TYSSE project.

Infrastructure Ontario (IO) is a state-owned enterprise (referred to in Canada as a Crown agency) overseen by the Ministry of Infrastructure and serves as the primary procurement lead for major public infrastructure projects using public-private partnerships. IO also manages the province’s real estate portfolio, provides long-term infrastructure loans to public sector clients, and provides assistance for commercial projects. IO has taken on a greater role in public transit projects amid the region’s shift towards utilizing P3s. IO is currently delivering the Eglinton and Finch West light rail projects using DBFM procurements. While IO and the P3 approach was intended to help the region deliver transit projects more cost effectively, construction costs have continued to rise, with cost estimates for the next wave of proposed subway lines far outpacing the TYSSE project on a per-mile basis.525

System Overview

TABLE 16: TRANSIT LINES PROFILED IN THE TORONTO REGION

*A single delivery method is not always used on an entire project.

** Projected costs for unfinished projects 526

*** Projected opening dates

The Toronto subway is part of a larger public transportation network, including streetcars, buses and light rapid transit, run by the TTC. The subway was the nation’s first, opening in March 1954. Since then, it has grown from a single, 12-station line running 4.6 miles beneath Yonge Street to a four-line system encompassing 75 stations over 47 miles. In 2019, the TTC recorded 236 million passenger trips on the Toronto subway.527

The Sheppard Subway line was completed in 2002 and it continues to be owned and operated by the TTC. It consists of four new stations and one reconstructed station— Sheppard-Yonge—where Line 4 intersects with Line 1. The Sheppard Subway is less than 4 miles from beginning to end, is completely tunneled, and was constructed using a mix of cut-and-cover (for the stations) and bored tunnel. It was completed using a conventional DBB contracting method.528

In 2017, Toronto completed a major extension of its busiest subway line, Line 1, known as the Toronto-York-Spadina Subway Extension (TYSSE). The TYSSE is a short 5.3 mile extension consisting of twin bored tunnels and six new stations constructed using cut-and-cover methods. The TYSSE was projected to cost about $1.7 billion but wound up costing $3.1 billion an overrun of 82 percent.529

The recently completed subway projects in Toronto are the most expensive ever built in the region. An April 2020 study analyzed a variety of potential cost drivers amid escalating transit construction costs in the region, finding that tunnel and station depth had major impacts on cost, though are not the only contributing factor.530 Though subways cost more to build, interviewees noted that there is significant pressure in the region to put transit underground to not only avoid surface disruption, but also because of a persistent perception that subways are inherently “better” than above-ground options. In particular, many political officials feel that subways will spur more development and place a suburb or neighborhood “on the map.”

Two new light rail lines are currently under construction. The Eglinton Crosstown (Line 5) will serve 25 stations along 12 miles of track, of which 6.2 miles will be below ground. Originally expected to open in September 2020, the line has been delayed to 2022. The project is estimated to cost $4.3 billion ($358 million per mile).531 The Finch West LRT (Line 6) will serve 18 stops (16 above grade) along 7 miles is expected to be completed in 2023 at a cost of $2.1 billion ($300 million per mile).532

Planning is also underway for four new proposed subway projects—the 9.6 mile Ontario Line, 4.7 mile Scarborough Subway Extension, 5.7 mile Eglinton Crosstown West extension, and 4.6 mile Yonge North Subway extension. As illustrated in Table 16, current construction cost estimates proposed lines based are significantly higher on a per-mile basis than the TYSSE project.533

Fraught transit governance that is subject to significant political interference can result in expensive low priority projects and significant delays, cancellations, and change orders.

Over the last decade, significant changes in governance—particularly the creation of Metrolinx—affected the region’s capacity to deliver projects. The region’s two most recent subway projects were largely built due to political pressure from suburban officials, and against the technical advice of experts.

The Sheppard Subway is the newest subway line in Toronto. It was initially proposed by the TTC in 1985, but rising cost estimates for the project and changes in provincial leadership led to its consistent delay and near-cancellation.534 Much of the political impetus for its eventual passage was from Toronto Mayor Mel Lastman, who previously served as Mayor of North York (a suburban district in northern Toronto served by the Sheppard Subway) from 1973 to 1997 when it was its own municipality. Lastman successfully lobbied the province and TTC to fund the Sheppard subway even though the agency’s technical studies found the line would be best served as light rail.535 The mayor and other political supporters were heavily in favor of a subway to help spur commercial development that would make part of North York into a “second downtown.”

The TYSSE project has a similar origin story. Political leaders wanted the city of Vaughan to be served by a subway line, not only to raise the profile of that area but to also spur development and raise property values around York University. Both the city and York University lobbied the province to fund an extension of Line 1 to Vaughan which, at that time, was not the priority of the TTC or other local officials in the region. In fact, the extension was deemed unjustified by the TTC due to low densities along the proposed route and modest projected ridership.536 However, Greg Sorbara, the former Minister of Finance for Ontario who represented Vaughan in the provincial parliament, successfully lobbied the provincial and federal government to push ahead with the project.537

Political influence and interference in major projects have persisted in the region, despite governance changes. Metrolinx was originally intended to serve as an independent, regional organization at an “arm’s length” from local and provincial politics, but its financial and governance structure made the agency largely captive to the political dynamics of the province. Reports and interviewees have documented a lack of political legitimacy and accountability around transit decision-making.

While Metrolinx is tasked with developing and executing regional transit plans, it does not have the authority to raise its own revenues. There is also no regional governing body in the GTHA that lies between the municipalities and the province to whom Metrolinx can be held accountable.538 Rather, Metrolinx reports solely to the Province of Ontario, who retains the final say in all decisions. The projects included in Metrolinx’s first regional transit plan in 2008 were also largely already decided upon by Toronto (through Transit City) and the Province of Ontario (through its MoveOntario 2020 plan for 52 rapid transit lines).539

Metrolinx itself is subject to significant political interference. Changes in political leadership can lead to projects getting modified or canceled even after construction has begun. The 2007 “Transit City” proposal put forth under former Mayor David Miller called for the creation of seven new light rail lines in Toronto.540 Initial studies for many of the lines were underway and construction had already begun on the Sheppard East line when newly-elected Mayor Rob Ford cancelled Transit City on his first day in office.541 Ford pushed instead to extend the Sheppard subway to Scarborough and replace the aging Scarborough RT line with an extension of the Bloor-Danforth subway line.542 Despite this cancellation, the Toronto City Council ultimately voted to resume work on Transit City in 2012, specifically on the Eglinton and Finch lines, which are now under construction.543

Similarly, the Province of Ontario approved $800 million in funding for a 9 mile light rail line in Hamilton (22 miles southwest of downtown Toronto) in 2015 under Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne.544 The Hamilton LRT was one of Metrolinx’s priority projects under the Big Move, and was expected to be opened in 2024.545 However, after an independent cost estimate showed project costs rising from $800 million to $4.5 billion, Conservative Premier Doug Ford, who succeeded Liberal Premier Wynne, canceled the project in 2019, before procurement was complete.546

The cancellation sparked significant backlash from opposition parties and debate between officials from the province and Hamilton, specifically over the accuracy and timing of the cost estimate used to justify cancellation. The $4.5 billion cost estimate also included operating and maintenance costs that were not included as part of the original $800 million estimate, which only covered capital costs.547 Debate surrounding cost overruns on the project were further complicated after a report by the Ontario Auditor General (AG) found that Metrolinx and the Ministry of Transportation knew, but failed to disclose, that the project would cost more than the initial $800 million as early as 2016.548 In February 2021, the province recommitted to a slightly shorter version of the project, offering $830 million in funding if the federal government agrees to commit $1.2 billion.549

Persistent political interference casts significant uncertainty over transit planning and decision-making in Toronto. The frequency by which political officials can cancel, modify, or otherwise interfere with projects that have already been approved or even under construction makes it difficult for the public and business community to assess the stability of any decision or plan introduced by Metrolinx. A 2018 report by the Ontario AG found that politically motivated project changes and cancellations have amounted to nearly $104 million in sunk costs for the agency.550

The lack of a standard, transparent process by which projects are proposed or evaluated was cited as one of the reasons why Metrolinx is susceptible to political influence. Despite formal business case analyses and other evaluations carried out by Metrolinx and IO, stakeholders and politicians propose a variety of different projects, with little to no structure on how to evaluate and vet these proposals.

Metrolinx has institutionalized a policy to require business case analyses for major capital projects over $42 million (50 million CAD).551 These analyses evaluate the rationale, value for money, and impacts of major investments during various stages of project development. These business cases also analyze the viability of various alignments and modes, deliverability of a project, and the level of expected project risk, among others.

However, what appears to be a streamlined and robust process for decision-making from the outside masks the largely political decision-making process that happens behind-the-scenes. This process was characterized by one interviewee as “decision-based evidence making” with political officials making a decision to move ahead on a given project, and planners or consultants being tasked with justifying the decision. While interviewees acknowledged that there are some sound technical reports and analyses prepared by Metrolinx, they expressed doubt over whether they are actually read or taken into account by political officials who have the ultimate say in approving projects.

Reports from the Ontario AG identified several instances of Metrolinx undermining its own decision-making and technical analysis process. As part of the Transit City project, Toronto, Metrolinx, and Ontario had already agreed to build the seven proposed projects as light rail lines, and Metrolinx’s 2009 business case analyses of these seven corridors did not assess the viability of alternate modes like BRT. When updating its business cases for the Finch West, Sheppard East, and Hamilton LRT lines in 2014, Metrolinx found that BRT service may be able to achieve similar benefits at a lower cost, and called for additional study of the cost-effectiveness of BRT versus LRT.552 However, the agency did not ultimately conduct any additional analysis. In January 2020, Metrolinx voted to move ahead with an eastern extension of the Scarborough subway and westward extension of the Eglinton Crosstown line despite receiving a cost-benefit-analysis report that found the projects would cost nearly $10 billion to build, but only result in $4.2 billion in benefits.553

Similarly, when assessing the overall benefit of LRT versus BRT in Hamilton, Metrolinx found that light rail would offer the most benefits under a high intensity land use intensification scenario, while BRT would perform best under moderate land use intensification.554 However, while Metrolinx modeled the benefits of LRT under low, medium, and high land use intensification scenarios, BRT was only studied under the medium intensification scenario. Metrolinx recommended conducting an updated business case before a final decision was made, though no additional study was conducted before the province approved the LRT project in 2015.555

In another case, Metrolinx overruled its own recommendation against building two new GO Transit stations after receiving pressure from the province and Toronto.556 As part of a planned expansion of the GO commuter rail system, Metrolinx conducted a business case evaluation of 17 proposed GO stations in 2016. The analysis did not recommend building stations in Kirby and Lawrence East (among five other rejected stations), finding that their inclusion would increase travel time and thus reduce ridership, lead to an increase in automobile use, and decrease overall system fare revenue.557

However, the agency subsequently modified its evaluation of the stations to make the Kirby and Lawrence East appear to score better and overrode their own recommendation to approve them after the then-Minister of Transportation and the city of Toronto pressured the agency to include the stations.558 The Kirby station resided within the electoral district represented by the then-Minister of Transportation in the Ontario Parliament, while Lawrence East was one of the proposed stations under the Toronto Mayor’s signature SmartTrack commuter rail expansion plan.559

Pursuing public-private partnerships for major projects just to save money produces mixed results.

In response to cost overruns and delays on major public works projects, the region moved towards using public-private partnerships for large infrastructure projects, largely managed by IO. The provincial government requires all public infrastructure projects over $83 million ($100 million CAD) to be screened as potential P3 candidates by IO.560 Under the Ontario P3 model, referred to as alternative finance and procurement (AFP), Metrolinx establishes project scope, budget, and purpose, while a private consortium finances and carries out construction (in some cases also the maintenance and operation).

IO was primarily used to deliver infrastructure like hospitals, schools and courthouses until 2009, when it began managing roadway and transit projects. After the completion of the TYSSE, project delivery was handed over to Metrolinx, which used IO to help deliver three light rail lines using P3s (primarily using a combination of design-build-finance-operate and/or maintain), including the Eglinton Crosstown, Finch West LRT, Hurontario line, and several expansions of the region’s commuter rail network.

The recent embrace of P3s is driven by a perception that they can alleviate many of the cost and schedule issues on projects and lead to more efficient project delivery. However, many interviewees were skeptical that the shift to P3s has done much to address the region’s cost issues for transit, despite IO’s previous success with other building projects. For example, the final bids on the Hurontario LRT, which runs in Mississauga, Ontario west of downtown Toronto, came in nearly $500 million (12 percent) higher than the original cost estimate of $4.1 billion, despite Metrolinx reducing the project’s scope through a shorter alignment and fewer vehicles.561 The increasing cost could be a result of shifting such significant amounts of risk to the private sector, which ultimately becomes priced into their bids through higher contingency budgets. Other interviewees suggested that the region may ultimately revert back to using more traditional forms of project delivery.

A major 2014 report by the Ontario AG found that IO’s methodology for calculating project risk and comparing the value-for-money between traditional and AFP procurements almost always favored the use of AFPs.562 As part of its cost comparisons, IO assessed how much project costs would be reduced if project risk was transferred from the public sector to the private sector under AFP. According to IO’s methodology, project risks were nearly five times higher under traditional procurements than AFP. In nearly all of the projects reviewed by the AG, it was only the assessment of risk transfer that led to AFP scoring better than public sector procurement. For example, IO estimated that delivering the four approved Transit City LRT lines as an AFP would cost $12.5 billion, versus $10.7 billion, a difference largely explained due to higher cost of private sector financing.563 This higher cost was offset by an estimated savings of $4.9 billion in risk that the public sector would not be responsible for.564

However, the AG’s report also found that IO did not use empirical data to back its assumptions of risks, and often painted public sector procurement in a bad light. For example, IO estimated that a traditional public sector procurement would result in a 29 percent cost overrun risk for the Transit City LRT lines, while an AFP procurement would have just a 2.5 percent overrun risk, an estimate the AG found unjustified by any evidence. While the report included recommendations and changes that are currently underway for future procurements, interviewees cited continued issues with risk assessment and alleged cost savings under P3s. All of IO’s transit projects are currently under construction or in development, so their performance relative to public sector procurements has yet to be fully evaluated.

Cost and timeline issues have been the subject of increased cov erage on the Eglinton Crosstown LRT. The project fell behind schedule in 2017, but under the AFP contract, Metrolinx had limited ability to hold the private consortium a ccountable for delays discovered early in the project as long as the conso rtium could certify it would meet the September 2021 opening target. 565 Remedies for delays could only take effect if the consortium itself, rather than Metrolinx, declared it could not meet its target opening date.

Additionally, the Ontario AG found that the risk of cost and timeline overruns were not entirely transferred to the private sector for the Eglinton Crosstown LRT, despite the premium paid for the P3 structure. In February 2018, the consortium filed a claim against Metrolinx requesting compensation and a deadline extension, arguing that Metrolinx did not provided the assistance necessary to address the delays.566 Metrolinx and IO reached an agreement to pay the private consortium $200 million—nearly half of the project contingency—in order to retain a September 2021 opening date. However, the auditor found that neither Metrolinx nor the consortium could provide detailed documentation that justified the settlement amount and the consortium’s claim that Metrolinx was partially responsible for not offering assistance to overcome the delays.567 In February 2020, Metrolinx announced the project would not be completed until well into 2022, noting that the private consortium had only achieved 84 percent of its target completion.568

Subjecting transit projects to their own, streamlined environmental assessment process speeds delivery.

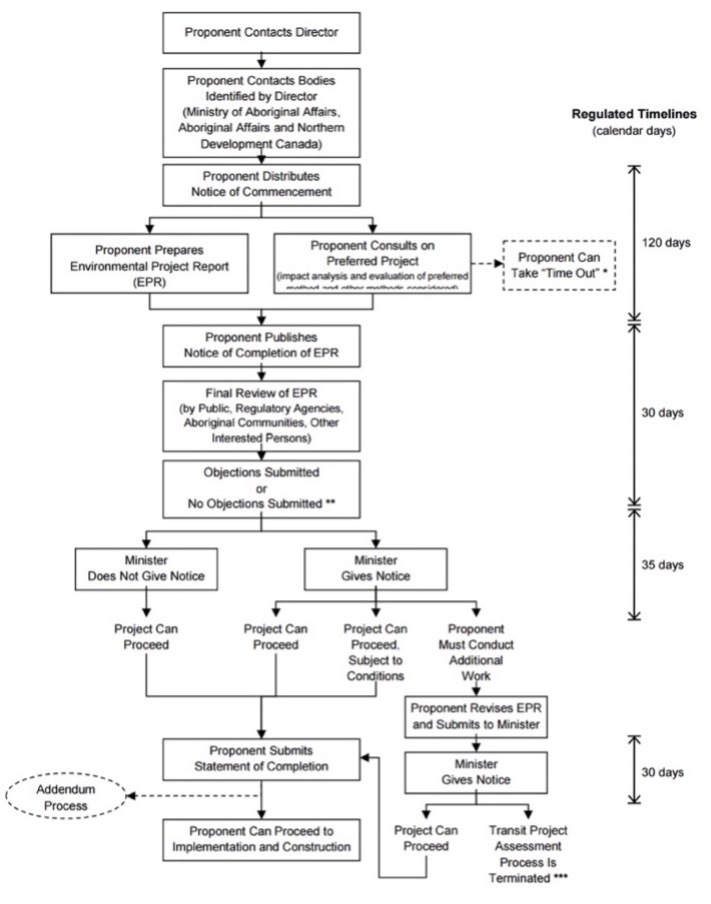

FIGURE 16: TPAP PROCESS AND TIMELINE 569

Public transit projects in Ontario are no longer subject to the full environmental assessment act. Instead, they are subject to a specific, expedited environmental review process designed in 2008 specifically for transit, called the Transit Project Assessment Process (TPAP).570 The TPAP serves as a self-assessment for transit projects and is primarily driven by the project sponsor.

The TPAP does not require project sponsors to conduct an alternatives analysis, but rather begins with a selected project. The TPAP guidance includes recommendations for project sponsors to conduct as much early planning work as possible to establish project scope and secure support from stakeholders, but this planning work is not a formal part of the TPAP.571

The TPAP also does not specify any technical studies that must be carried out for a project, though other regulatory agencies may request that project sponsors conduct specific studies (i.e., noise and vibration analysis, cultural heritage assessments, financial analysis, etc.). These studies can vary based on the project type and characteristics. The Ministry of Environment recommends project sponsors contact regulatory agencies early in the project planning phase to determine their specific information needs.

Once a project sponsor identifies a project and issues its notice of commencement, it has 120 days to complete a draft Environmental Project Report (EPR). During this period, project sponsors consult with affected parties, regulatory agencies, and Aboriginal groups. If the project sponsor encounters an issue that requires additional study or could jeopardize the 120 day time limit, it may utilize a “time out” provision to temporarily pause the clock. Time outs can be utilized in two cases: negative impacts on a matter of provincial importance, or potential negative impacts on a constitutionally protected Aboriginal or treaty right.

After completion of the EPR, the public has 30 days to review the document and submit comments and objections in writing to the Minister of the Environment. Objections must be submitted in writing and include description of why further study is needed, documentation of negative impacts on matters of provincial importance or affecting Aboriginal rights that were not identified in the EPR, and a summary of how the person(s) submitting the objection has been involved in the project’s consultation process.

After the public consultation phase, the Minister has 35 days to review feedback and consider whether the project will have a negative impact on either a matter of provincial importance or constitutionally protected Aboriginal or treaty right. After this period, the Minister can issue one of three notices: 1) a notice to proceed with the project as planned in the EPR; 2) a notice to require the project sponsor to take further steps like additional studies or consultation; or 3) a notice to allow the project sponsor to proceed with the transit project subject to specific conditions. When the Minister issues a notice requiring additional steps to be taken, the project sponsor must prepare a revised EPR. If the Minister still feels that a project does not appropriately address negative impacts, they can terminate the TPAP and require the project to comply with the full Environmental Assessment Act. If the Minister does not issue any notices within the 35-day period, the project may proceed as planned.

Ontario has taken further steps to streamline the environmental review process, including through 2020’s Building Transit Faster Act.572 The act applies only to the province’s four priority transit projects—the Ontario Line, Eglinton West LRT, Scarborough subway extension, and the Yonge North subway extension—and includes several provisions aimed at speeding up project timelines. For example, it eliminates “hearings of necessity” for property acquisition. These non-binding hearings were previously required to determine whether a property acquisition was fair and necessary for a given public project.

The new law also provides for an “enhanced process” to order companies to relocate utilities. Once ordered to relocate, utility companies must enter into negotiations with Metrolinx “reasonably promptly,” and make a reasonable effort to acquire all necessary permits. If the utility company does not comply, Metrolinx may ask the Ontario Superior Court to consider ordering the company to carry out the relocation. The provision also requires utility companies to reimburse Metrolinx for losses or expenses that result from their non-compliance with a relocation order.

It also addresses permitting by granting officials the ability to enter transit corridor lands to remove obstacles without the consent of property owners, as long as proper notice and compensation is provided. The Minister of Transportation is allowed to grant Metrolinx the authority to close streets or access city services (i.e. water or sewers) if an agreement cannot be reached with the municipalities. And in an attempt to minimize conflicts between transit projects and private construction work, private property owners living within 98 feet of a corridor designated for one of the four priority transit projects must receive a permit from Metrolinx to carry out any construction work, including home repairs.573

The province also issued a separate regulation creating a streamlined environmental review process for the Ontario Line. The process is largely similar to the TPAP, but allows select early works—like utility relocation, station construction, bridge replacement, or rail corridor expansion—to be carried out before the completion of the full environmental assessment.574 This regulation created a separate category of “Early Works Reports” narrowly tailored at evaluating the scope, alternatives, and potential environmental impacts of these activities.

Several interviewees felt that these reforms to the environmental review process have helped minimize conflict and expedite project approvals, with environmental clearance and community consultation being completed within two years. These reforms have operated under the general premise that transit is inherently beneficial for the environment, and therefore should not be subject to a lengthy and potentially contentious environmental clearance process. However, these reforms—along with other proposed changes to province-wide environmental review—have come under scrutiny from environmental groups concerned that they have excessively curtailed opportunities for the public to comment or raise concerns over projects.575 Others expressed concern that the Building Transit Faster Act may erode the environmental review and stakeholder engagement process, which is already streamlined for transit projects under the TPAP.576