New York City: Second Avenue Subway

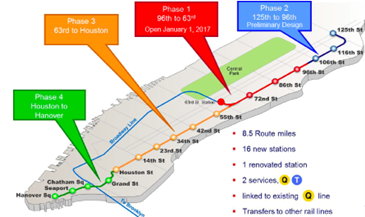

The Second Avenue subway is New York City’s most ambitious subway expansion in more 50 years. The project dates back to the 1920s when the city first announced it was replacing an elevated rail line with a new subway. The project was mothballed until the 1970s when several tunnel segments were constructed; however, those tunnels were abandoned due to a lack of funding. In 2004, an environmental impact statement was completed, the project separated into four separate phases and in 2007 construction began on the first phases.

This first phase opened to public in 2017, extending the existing Q line from 63 Street to 96 Street on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. The project cost approximately $4.5 billion. On an average weekday in 2023, subway ridership exceeded 21,000 at 72nd Street, 16,000 at 86th Street, and 12,000 at 96th Street.

Construction of the second phase has not yet begun. It will extend the line north from 96 Street to 125 Street in East Harlem.

Table of Contents

Photos and Map

The four subway phases. Source: MTA

Construction required replacing numerous utility lines. Source: Wikipedia.

New Station at 86th Street. Source: MTA

Project Team

The MTA Capital Construction Company, a subsidiary of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), led the construction of the first phase. The Capital Construction Company was formed in 2003 to build the MTA’s largest subway and railroad projects.

The MTA’s New York City Transit Authority operates and maintains the city’s subways. For the first phase of the Second Avenue subway, the Transit Authority’s Capital Program Management department was responsible for the engineering, and it managed a team of consultant engineers. The first phase was a design bid build project.

WSP was the project’s consultant construction manager, responsible for overseeing the work of contractors.

For the second phase, the MTA Capital Construction and Development Company (its name was recently changed from MTA Capital Construction) is leading both the engineering and the construction. It will be a mix of design build and design-bid-build contracts.

This document refers to the following project management staff.

- Michael Horodniceanu, former president of MTA Capital Construction.

- Bill Goodrich, former senior vice president and executive vice president at MTA Capital Construction.

- Tim Gianfrancesco, former MTA Capital Construction’s deputy vice president and deputy project executive.

- Tom Peyton, former senior engineering manager at the WSP consulting firm, who served as the project’s construction manager.

Design and Construction Challenges

Building the Second Avenue subway was expensive, complicated, and disruptive. Construction workers had to dig up streets and then move utilities including sewer, gas, water, electricity, telephone, and steam. MTA Capital Construction president, Michael Horodniceanu, said relocating the lines while trying to minimize outages to utility services was like “trying to ride a bike and change the tire at the same time.”

The MTA dug tunnels, built underground caverns, laid tracks, and installed signal systems. New stations were built along with stairs, mezzanines, and elevators. The subway incorporated components that were far more sophisticated than subways built in previous generations. For example, each station had 19 different communication systems including those relating to intercoms, intrusion detections, closed-circuit television, service announcements, telephones, emergency booths, police and fire radios, emergency broadcasts, and fire-alarm/pull stations.

The design required an endless number of decisions such as station location, the number of entrances, the depth of stations, the number of tracks, and the width of platforms. No cookie cutter design exists when building a subway in one of the world’s most densely populated neighborhoods.

The designers had numerous external stakeholders including residents, businesses, media, and elected officials. Just as complicated were its internal stakeholders. For example, six different divisions in NYC Transit Authority’s sprawling bureaucracy submitted a detailed and extensive list of employee facilities that they wanted at the new stations.

Despite the MTA’s extensive precautions, subway construction disrupted the lives of businesses, residents, drivers, and pedestrians. Water, electricity, cable, and telephone service were periodically halted. Construction workers installing equipment accidentally flooded the basement of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Two years after construction began, more than 90 percent of fifty-nine businesses polled near the construction said their sales were down, and nearly half had to lay off workers.

Horodniceanu’s motto was, “You have a plan, and it changes on Day One.” For example, a 450-foot long tunnel boring machine was used under Second Avenue. But not long before the machine was fully assembled and deployed, advance probes found soil and crumbly rock zone just past the launch area, not something the boring machine was designed to dig through. If it kept going, apartments buildings could have collapsed. After numerous meetings, Horodniceanu’s team decided to drill a series of 80-foot deep holes where workers inserted steel pipes and pumped in a liquid chilled to thirteen degrees below zero to freeze that zone, allowing the tunnel boring machine to safely mine through it.

Project Team: Descriptions

Michael Horodniceanu

Michael Horodniceanu

Michael Horodniceanu was president of MTA Capital Construction Corporation between 2008 and 2017. He had previously been the chairman and CEO of an engineering and planning firm, and New York City DOT’s traffic commissioner. He had a bachelor’s degree in engineering, a master’s degree in management, and a PhD in transportation planning and engineering. (Photo per LinkedIn)

When Horodniceanu told Eno his highest annual salary was $341,000, he noted that the CEO for the Crossrail project in London earned approximately $700,000 one year.

Horodniceanu identified the following impediments to effective project management

- Lack of training in management techniques (finance, communications, leadership, negotiations)

- Lack of authority

- Too many projects

- Lack of commitment

- Lack of people skills

- Lack of knowledge about the client

- Lack of participation during negotiations

Bill Goodrich

Bill Goodrich

Between 2008 and 2018, Goodrich was the senior vice president and then executive vice president at MTA Capital Construction with full responsibility for the design, construction, and commissioning of the Second Avenue subway and the multi-billion dollar project that connected Long Island Rail Road with Grand Central Terminal.

Goodrich has a bachelor’s and master’s degrees in engineering. Over a long career, he has held numerous engineering and management roles including leading construction of nuclear power plant units, a resident engineer for the Big Dig project, and vice president at Parsons Brinckerhoff where he provided construction management services for NYC DOT and MTA projects.

When Goodrich worked on the Big Dig, he learned that on such large projects, someone could start in an entry level position (e.g., field inspector or field engineer) and spend a significant percentage of their career on that one project. Those individuals would learn as they go, gain experience, and become a valuable asset to the engineering and construction industry.

In 2008, Goodrich was working as a consultant for the MTA when Horodniceanu offered him the position as the program executive in charge of the Second Avenue subway. Goodrich saw it as a “great opportunity to join the client organization and lead a major program.” The MTA’s pension program was very appealing, something that he was not getting in the private sector.

He was also offered a higher salary than he was earning. In 2013, Goodrich became the 58th highest paid employee at the MTA with a salary of $200,909. Keep in mind that the MTA had more than 71,000 employees at the time.

Tim Gianfrancesco

Tim Gianfrancesco

Tim Gianfrancesco was MTA Capital Construction’s deputy vice president and deputy project executive for the first phase of the Second Avenue subway. His background and experience made him an ideal candidate to helped lead the design and construction of a new subway line under Manhattan’s streets.

Gianfrancesco was hired in 1989 as part of the “Transit Corps of Engineers” program. The state established this program to attract young engineers to the NYC Transit Authority. Each year, the program selected 30 upper division students from college engineering programs. If students took positions at the Transit Authority, they would be reimbursed for their college tuition (less any amounts received from scholarship) over a four year period. The program was discontinued after a few years.

Upon graduation, Gianfrancesco decided to work at the Transit Authority, in part because the salary and benefits (including the tuition reimbursement) were more lucrative than his other offers. When engineers started in this program, they attended job development lectures and classes, and had frequent interactions with senior leadership who helped develop career advancement goals. This early career coaching and professional contacts opened up opportunities within the engineering and construction groups at the Transit Authority.

Early in his career, Gianfrancesco worked on a variety of projects including pumping systems, ventilation fans, and tunnel lighting. He designed subsurface utilities including power and communication ducts, sanitary and storm sewers, and water mains.

In New York City, most of the underground utilities are owned by private firms (e.g., cable, phone, steam, gas, and electric companies) and the City of New York (e.g., water and sewer). There were two primary reasons why the transit agency needed to design elements related to utilities it did not own. First, the subway tunnels and stations were adjacent and below utility lines, and subway projects could impact those utilities. Second, when a Transit Authority project required a utility line to be moved or replaced, the agency was historically and legally responsible for all the associated design and construction costs.

Additional underground space was often needed when installing new communications systems, exhaust systems, elevators, and other subway components. These projects could impact not only utilities, but also adjacent building foundations.

After Gianfrancesco obtained drawings and maps of existing utilities and subway structures, he would figure out where contractors could excavate and build out space while minimizing impacts and costs. Design was challenging because the maps did not always indicate the correct location of utility lines, and construction was challenging because of the need to minimize any utility outage.

Gianfrancesco learned how to manage numerous external stakeholders including residents and local businesses, and those who worked for the City of New York and the utility companies. All this experience would prove invaluable because the most complicated aspects of building a new subway line under Second Avenue related to utilities and constructing below and adjacent to residential and commercial structures.

As he moved around and up in the organization, he worked on increasingly more complicated reconstruction and expansion projects such as the reconstruction of the 1 and 9 subway lines at the World Trade Center, and the new South Ferry station and Fulton Street Transit Center. These projects provided Gianfrancesco with valuable experience directly related to the challenges that he would later face building the new concrete tunnel and station structures for the Second Avenue Subway. He also worked on another subway expansion project, the 63rd Street Connector, where he learned about other construction techniques applicable to Second Avenue, including building slurry walls.

Tom Peyton

Tom Peyton

As a senior engineering manager at the WSP consulting firm, Tom Peyton served as the project director for construction of the Second Avenue subway. WSP was the project’s consultant construction manager, responsible for overseeing the work of contractors on behalf of the MTA Capital Construction Company.

Peyton was responsible for providing WSP’s services which included resident engineering and inspection, constructability reviews, contract management and administration, project controls, utility coordination, commissioning, and startup. During much of the construction period, WSP had an average of 120 people on the site, managing up to eight construction contracts simultaneously.

Peyton had previously served as construction manager on other major projects including a water tunnel in Massachusetts. He has a bachelor’s degree in engineering as well as an MBA, and he had extensive tunnel construction experience using numerous techniques under a wide range of underground conditions.

When he managed the Second Avenue subway project, he talked with his team and construction firms every morning to find out what happened the night before. Looking at work summaries and dashboards, his team planned and monitored all the work that was expected to occur that day and week. He said, “I was always ready to have a Plan B. Not only in the morning, but throughout the day. If something doesn’t happen, you need to find out why and figure out how to catch up.”

Attributes, Skills, and Experience of a Good Project Manager

Horodniceanu described some of the key attributes he sought when hiring project managers. First, he mentioned a strong technical background. Second, he said, “Desire is a key ingredient.” He explained that a candidate needed to be excited about taking on a challenging position and motivated by other factors besides money. Third, he looked for someone who was “willing to learn.”

When interviewing candidates, he looked for someone who was honest, a person who likes people, and a willingness to be humble and allow others to take credit for the agency’s accomplishments.

He identified the following attributes of a “great” project manager. Although the list was facetious, it reveals the extraordinary challenges that project managers must face.

- Intelligence of Einstein

- Integrity of an Apolitical Supreme Court Judge

- Patience of a Saint

- Negotiating Skills of a Horse Trader

- Savvy of James Bond

- Planning Skills of a General

- Communication Skills of Walter Cronkite

- Drive of Bill Gates

- Tough Skin of an Armadillo

- Ego of Mother Theresa

Obviously no one can meet the standard above. So, Horodniceanu identified the following attributes of a “quality” project manager:

- Follow through on all commitments

- Backs team members decisions

- A good listener

- Organized

- Proactive

- Technically proficient

- On top of all project aspects

- Handles multiple tasks and prioritizes well

- Leads by example

- Delegates well

- A good communicator

- Holds people accountable

Goodrich discussed the difference between a project manager and a construction manager. He said managing a project requires different skills than managing construction. Project managers, he said, have certain technical knowledge, but what they are being asked to do is to manage contracts. “It’s more pure contract administration,” he said.

Referring to Peyton’s role as construction manager, Goodrich said, “Tom Peyton is a tunneling guy. He spent his whole career on tunneling projects. He knows everything from rock mechanics to tunnel boring machines, and how contractors will look at and execute jobs. It’s a different skill set. More hands on with the technical part of the work.”

Recruiting and Retaining

When the MTA Capital Construction Company was first established in 2003, Goodrich said the new agency brought in many employees from the NYC Transit Authority. “By the time I got there in 2008, most recruitment was from the outside. We would advertise and interview internal candidates, but more than 50 percent were from outside the MTA. Oftentimes they had more experience, skills and knowledge. It’s too bad. It would have been nice to give people from other MTA agencies the opportunity. If they spent their whole career and never got training or only a limited opportunity to even get outside training, they wouldn’t be as developed as a consultant or contractor.”

Goodrich identified three things that attracted many people to the MTA Capital Construction Company. The first was the opportunity to work on large projects. Second was the pension. Third was the opportunity to make decisions as a client, not someone who recommended decisions as a consultant.

Goodrich said, “When hiring someone in their 30s and 40s, they are more likely to think about pensions and retirement. Talking to a 21 year old about retirement, that’s such a foreign concept. It falls on deaf ears. Pension is more of a factor for mid-career people.” He said he thinks that job security is also more important when someone is in their 30s and 40s.

Gianfrancesco noted that when hiring project managers, a candidate’s certifications and education do not necessarily indicate whether that individual would be a good project manager.

He relies on references and someone’s reputation, and wants to know exactly what work a person did on a project. He said, “Not just how many projects someone worked on, but how much work they did. Did they jump around and work on different projects but have only small roles? When someone works on a project from beginning to end, you know they stuck it out and moved up through stages.”

Gianfrancesco said a project manager on a large transit project does not necessarily need to be an engineer; it depends on the project and what the challenges will be. Some managers could have a project management background or have been a contractor with technical experience, but not have an engineering degree.

Gianfrancesco pointed out the importance of understanding scheduling. The Second Avenue subway needed a scheduler for each project component and then someone at the top to understand how each schedule fit into the overall programmatic schedule.

Gianfrancesco also noted the difference between managing a design-build (DB) and a design-bid-build (DBB) project. He believes it is easier to go from managing a DBB project to a DB project, but not necessarily, the other way around. He explained how DB project manager’s role is more about administering contracts, while for DBB, project managers are more involved in the design and therefore need to be more technically capable.

Retaining and Promoting

Interviews with former MTA officials revealed the following issues relating to retaining engineers and project managers.

i. Reducing Staff Led to Lower Morale and Fewer Project Managers In recent years, the MTA has reduced staffing levels through attrition. When the MTA began undertaking design of the Second Avenue subway and other megaprojects, agency leaders decided to fill the engineering gap with consultants, rather than permanent employees. This was seen as a way to save money and provide greater flexibility in staffing levels. However, it had two major long-term negative consequences. First, it reduced the future availability of experienced and qualified project managers. Second, it hurt morale because the agency’s engineers spent less time on engineering and more time managing contracts.

ii. Not Enough Incentives Horodniceanu lamented that MTA’s engineers are unionized, and their salaries are determined by the union contract. As a result, he said they had little incentive to perform quality work: “If they make a lot of errors, they won’t get promoted. They could get punished but not rewarded. So, if you don’t do anything, you don’t get into trouble.”

Some experienced engineers choose not to get promoted to project management positions because the position may be less secure, the hours are longer, and they are no longer eligible for overtime. Engineers can sometimes earn higher salaries than their managers. Others choose not to go into project management because they enjoy the technical aspect more than the managing role.

iii. Pay Referring to project managers at the MTA and other public sector organizations, Peyton said, “They don’t pay them enough, no question about it.” Although he did say that a benefit of working in the public sector workers is having more vacation time. Gianfrancesco noted that the MTA provides a pension with good job security and a generous amount of personal time, sick time, and vacation time along with excellent health benefits. However, he has seen the salary difference widen between private sector and the MTA in recent years.

iv. Pensions The pension program for MTA employees has changed over the years and its benefits depend upon when someone was first employed. The program’s features offer a strong incentive to work at the agency for at least 20 years and most employees are eligible to begin collecting a pension once they reach 55 years old.

There are two reasons why MTA project managers are better off financially if they leave the agency once they reach their mid-50s to early 60s. First, they can collect a pension and also get a higher paying position for a private firm. Second, the spouse of a retired employee is eligible to receive pension payments; but, if the employee dies before retiring, the spouse will not receive any pension payments.

WSP’s Tom Peyton has noticed that experienced project managers in the public sector leave their organizations when they are eligible to receive attractive pensions. Private sector firms like to hire them because they can be used to win and lead the company’s next projects.

Role of Consultants

Horodniceanu, Goodrich, and Peyton offered their insight into the appropriate role of consultants in a large transit project.

The MTA Capital Construction Company was a lean organization when Horodniceanu was president. He proudly declared that its headcount was no more than 141 full-time people while it was responsible for building the Second Avenue subway and other large transit construction projects.

He did not want to hire too many people because it would have been too hard to fire them. Firing someone, he explained, required extensive documentation and if someone was older than 40 they could claim discrimination based on age. He said when hiring a full-time employee at the MTA, “it’s til death do us part.”

As traffic commissioner and the head of a private consulting firm, Horodniceanu knew the presidents and CEOs of many consulting companies retained by the MTA Capital Construction Company. He said his position gave him leverage. If a consultant was not performing, he would contact their bosses and they would find him someone else.

Goodrich believes the most efficient way to manage a project is with a blended team consisting of agency staff supplemented with outside consultants. He said that fits in with the approach taken by the large consulting firms WSP, HNTB and AECOM. He noted that Bechtel prefers to manage and be responsible for all facets of a project on behalf of their clients.

Goodrich said that consultants nearly always comprise more than half of a project’s staff. He explained, “You don’t want to hire and fire people. Consultants can ramp up and down on a project since they generally have other projects they can move staff to. It’s difficult though for agencies to send people to other projects after their projects are complete.”

Goodrich remembered that on the Second Avenue subway project, only 10 to 20 percent of the staff were agency employees; the rest were consultants including those who designed and managed the construction. The percentages changed over time. During the early stages of the project, MTA staff comprised about 30 to 40 percent. As the agency moved closer to construction, the consultants began comprising a higher percentage of the team.

He said, “Looking back, it was appropriate. Agencies should be able to manage contractors and consultants with that level of staffing. At the end of day, you need to rely on outside consultants and outside contractors for the bulk of the organization.”

Peyton praised the work of Tim Gianfrancesco saying that he had a thorough knowledge of the organization and how it worked. Gianfrancesco “listened, asked questions, and took advice.”

But, he said, “MTA Capital Construction didn’t have the experience to manage ten construction projects, simultaneously.” He noticed that the agency did not have anyone with enough experience building new tunnels and stations, working with major contractors, and understanding how everything fit together. He said, “Nobody had built a tunnel. It was not a skill set they had retained. It wasn’t just the size, but also the type of project. It’s different than changing elevators or escalators.”

Training

Goodrich, Gianfrancesco, and Peyton shared their insight about training issues.

Goodrich on training and experience

Goodrich talked about how training and retaining employees are connected. On the Big Dig project, the joint venture constructing the project organized a formal training program with mandatory human resources and technical training. All the engineers and managers were brought up to a certain level of expertise. He said, “As long as they were trained and had an opportunity for advancement, people were willing to stay.”

Goodrich said the Big Dig’s training programs and modules were tailored to the roles and levels of the employees. Some of the classes served multiple purposes. For example, learning about change order management taught employees how to handle change orders and familiarized them with the project’s contracts as well as its policies and procedures.

He said, “On large programs, you need a training element. There should be an ongoing review process at Human Resources that evaluates people. Who are the rising stars? Identify them and make sure they have an opportunity to advance in the organization.”

Goodrich said that most large engineering and construction firms have some sort of project management certification program. He said, “I believe it contributes to retention, as long as someone is learning and advancing, and is compensated fairly.”

He noted that MTA Capital Construction did not have a formal training program when he was there, but he thinks it should have had certification programs along with technical training for construction managers, project managers, and inspectors. Goodrich noted that MTA Capital Construction (where he worked) had significant organizational differences in terms of policies, procedures, and practices than the MTA’s NYC Transit Authority (where Gianfrancesco received the bulk of his training and mentoring.)

He explained one way that training can save an agency money. “There’s no question there’s a premium that contractors build into bids whenever they are doing work for the MTA. They know how effective or ineffective agencies are in managing projects and change orders. If the MTA wants to bring down costs, they should train internal staff to manage projects more effectively.”

Goodrich said, “Contractors get frustrated regarding change orders. It could be as much as 20 to 30 percent of a project’s cost. They know they’ll have to finance it, because of delays in getting paid for change order work. By the time they get all the approvals at the transit agency and get paid, they’ve had to pay labor and materials for all that time. If the project is managed more effectively and change orders are executed in a timelier manner, there’s no need, theoretically, to carry an additional cushion or premium.”

Eno asked Goodrich whether contractors earn more than they deserve because seasoned contractors can outmaneuver inexperienced transit agency project managers. He responded that it was unusual for that to happen because agency lawyers are typically part of a change order process. However, if the project manager is inexperienced, the contractors need to spend more time (and money) negotiating change orders.

Gianfrancesco on training

Gianfrancesco learned most of his technical skills from working with experienced people. Some skills were not taught at any engineering school. For example, he learned how to read utility company maps and then how to relate that to surveys of existing manhole covers, streets and sidewalks. He had to find and then decipher as-built drawings of subways that were constructed in the early 20th century.

Gianfrancesco was selected to be in a Transit Authority program for top performers who had demonstrated significant career potential. He attended the program’s three-day management course, and he was assigned a mentor who helped Gianfrancesco identify career paths.

Gianfrancesco took Transit Authority training courses, usually one or two days long, on topics such as communications, time management, cost management, cost controls, and schedule controls. He attended informal training sessions (such as a ‘lunch and learn’ with subject matter experts) and he took courses through the American Society of Civil Engineers and American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

Peyton on training and experience

Peyton said good project managers need to manage costs and understand how project elements fit together. He cited different experiences that helped him on his Second Avenue work.

He had developed schedules and cost estimates, and his engineering background gave him the skills needed to approach and solve problems. His contractor background gave him valuable construction experience. “It was easier to manage contractors because I was one.” He added, “I knew how to get labor to work with us, not against us.”

He understood from experience, what mobilization would look like, and what contractors could and could not do. He also had worked on projects with multiple contractors where he had to make sure that each contractor performed its work in a way that allowed other contractors to perform theirs, whether that work was done sequentially or simultaneously.

He credits the mentoring and experience he gained at a construction firm where he learned “what it took to be seen as an engineer, act the part, and be the part.” He said the firm encouraged him to hone his skills, insisting that he get his professional engineering license, and then paid for his master’s and PhD courses.

“Us gray haired guys have lots of experience. Every time you manage another project, you learn more.” He said he understood what the members of his team needed to do – from the resident engineers who talked to the doormen on a daily basis to the schedulers and cost estimators. “I understood all of these skills. I had developed them over time, and it made me a better, well-rounded manager.”

Transition from Phase 1 to Phase 2

The first phase of the Second Avenue subway opened in 2017, but construction has not yet begun on the second phase. According to Gianfrancesco, not many senior employees who helped manage the first phase are still working at the MTA.

Peyton said it was disconcerting that going into the project’s second phase, the MTA Capital Construction Company’s Second Avenue subway team lost its top people. He said, “Any good manager can manage a project. But, you need to know who to talk to and understand its idiosyncrasies.”

Peyton remembered when the MTA Capital Construction was trying to finish up the first phase, issues were raised by numerous operating groups (e.g., safety, maintenance, electrical). These departments had signed off on design documents years earlier but when they needed to give final approvals, technologies and standards had changed. The people who had given their original approvals were no longer in the same positions.

Gianfrancesco also noted that due to the long lag between phases, the project is losing institutional knowledge at the MTA and at its stakeholders. For instance, at the utility companies, officials learned a great deal about subway construction during the first phase, but transferring that knowledge within their companies is not their highest priority.

Goodrich noted that it would have been preferable to build the second phase of the Second Avenue, sooner. He said, “If no funding is available that smoothly takes you from phase 1 to phase 2, you can’t retain people. They’ll move on. In the private sector, they’ll move to other projects. In the public sector, they’ll go elsewhere.”

He said, “we had a great team feeling. We realized that we were doing something unique and getting all this experience. If we could have kept the team and consultants together, we would have had such a great opportunity to transfer and utilize that knowledge.”

Instead, once the new line was opened, the team was ready to close out contracts and move on. Goodrich noted, “It always comes down to funding.”

Lessons Learned

Gianfrancesco said there were various efforts to document lessons learned, but no formal compilation of them that was transmitted from the project’s first phase to its second phase. Gianfrancesco was in a position to know, since he was the deputy project director on the first phase and the project director for the second phase.

Many lessons, however, have been incorporated into the second phase. For instance, the MTA engaged some consultants who had worked on the first phase to set up design criteria and standards for the second phase. The MTA and its consultants also drafted technical advisory papers and talked to the utility companies about how the second phase could be performed better.

Although there was no single lessons learned document, some documents containing lessons learned were prepared. Based upon discussions with interviewees, these documents have not been widely shared within the MTA, let alone outside the MTA.

The MTA Capital Construction Company did prepare a folder of lessons learned. And Horodniceanu hired a consultant, Molly Gordy, to write a book about the Second Avenue subway; but the book was never finalized or released.

Peyton said he also prepared a lessons learned document. His firm, WSP, documented and submitted an extensive spreadsheet with details about both the positive and negative aspects of the project.

The MTA was hesitant to document lessons because according to one official, “you want to show that you’re improving, but don’t want to show that you did it wrong.” Some lessons are hard to formalize because an experience can be interpreted differently and taken out of context. For example, one lesson learned from the first phase was that the MTA should remove trees from a park as soon as it gets the permit to do so.

On Second Avenue, the MTA needed to remove trees in a park where it would be storing large equipment during construction. Once the city’s Parks Department provided a permit to remove the trees, the MTA started to mobilize a tree removal crew. But the community wanted the MTA to wait several months because the park space was not needed, yet. The MTA agreed to wait. However, when the time came for the trees to be removed, squirrels had begun nesting in them. The community got upset about removing the trees, which led to delays when the MTA tried to renew its permit.

The squirrel story demonstrated why revealing lessons to the public could harm an agency’s reputation. The MTA would be intensely criticized if the public learned that it wants to knock down trees because it fears that squirrels will start nesting in them. The editors at New York City tabloids would enjoy preparing headlines and graphics to accompany that story.

Goodrich said lessons learned should be documented at the ends of design, construction, testing, and commissioning. He added, “If they are memorialized in a document, it could be part of a training when getting ready for the next project.” He emphasized, “Lessons learned should be in a training program.”