Copenhagen

Copenhagen opened its first rapid transit system for service in 2002 with the completion of the initial segment of the 12.7 mile M1 and M2 lines, which serve 22 stations (the remaining stations were opened in 2007).414 Since 2007, the region has expanded its system by 11 miles and 19 new stations through two new lines, with additional extensions underway. Among the unique features of the Copenhagen Metro are compact, standardized station designs and short but frequent fully-automated trains, which help to keep costs low without sacrificing capacity during peak hours.

The Metro was funded largely using “value capture,” (using increases in land values due to new infrastructure being built) as part of a larger urban redevelopment effort, which is unique for transit projects of this scale, and is touted as helping to revive the region’s economy. Surplus revenues from operations funded nearly half of the construction costs for the initial segment of the Metro. Additionally, the Copenhagen Metro is operated by a state-owned corporation owned jointly by the national government and municipalities, which has been able to successfully build up an experienced project delivery staff in a short amount of time.

Table of Contents

Governance Overview

Major infrastructure projects in the region are primarily carried out by privately managed corporations often owned jointly by the national government and relevant municipalities. The Ørestad Development Corporation was the state-owned, special purpose corporation created in 1993 to redevelop Ørestad, a former military training ground in Central Copenhagen owned jointly by the Danish Ministry of Finance (45 percent) and Municipality of Copenhagen (55 percent).415 The Corporation was also tasked with building the initial phase of the Metro (the M1 and M2 lines), which was funded using value capture from the redevelopment of Ørestad.416 In 2007, the transit and urban redevelopment arms of the Ørestad Development Corporation were spun off into two separate entities: Metroselskabet and the Copenhagen City and Port Development Corporation.417

Metroselskabet is responsible for both constructing new lines and operating and maintaining the Metro. Ownership of the Metro is split between the Municipality of Copenhagen (50 percent), Municipality of Frederiksberg (8.3 percent), and the national Ministry of Transportation and Housing (41.7 percent).

Metroselskabet is governed by a nine-member Board of Directors. The Danish Government and Municipality of Copenhagen each appoint three members, and the Municipality of Frederiksberg appoints one member (along with one alternate member). The remaining two members are elected by the employees of Metroselskabet. All board members serve four year terms.418 Metroselskabet’s day-to-day affairs are managed by a CEO and a four-person group of directors. It contracts out the day-to-day operation of the Metro to Metro Service A/S, a joint venture between Azienda Tranporti Milanesi (Milan’s public transit operator) and Hitachi Rail STS.

A similar state-owned enterprise model is used for the Greater Copenhagen Light Rail project, which is being delivered by Hovedstadens Letbane, a publicly-owned company that shares its staff and CEO with Metroselskabet. This light rail corporation is owned by 11 suburban municipalities as well as the Capital Region (the Copenhagen regional government). All municipalities and the regional government have a representative on the company’s Board of Directors, which meets six times a year.419

In addition to serving as a partial owner of the Metro, the national government’s role is primarily to approve projects through the passage of construction acts in parliament, approving environmental review documents, and granting safety approvals, though the national government was responsible for granting building permits for the City Ring line. The Danish Parliament approves the national construction acts, which are required for all major infrastructure projects of national significance. The construction acts detail the alignment and proposed stations of a project, and delineate the roles and responsibilities of various authorities on the project (i.e. the Minister of Transportation, Metroselskabet, and the municipalities).420 Specific processes for handling land acquisition, construction notices, utility relocation, and complaints are also outlined in the construction act. Additional elements like working hours or acceptable noise levels are included in either the construction act or the project’s environmental impact report, which is adopted as part of the act. One the act is passed, it carries the weight of parliamentary approval, and all parties and stakeholders are bound to its terms and rules, providing an efficient way to hammer out all concerns and questions, as well as formally establish agreement on the rules and authorities of all parties.

The region’s municipalities serve as the authority for granting building permits for most major projects as well as helping prepare environmental review documents. Leaders and staff from the national government and municipalities also meet annually with Metroselskabet’s Board as part of a partnership meeting of the company’s owners, allowing public sector staff and representatives to stay aware of project developments and influence high-level decisions.421 The Municipality of Copenhagen retains dedicated technical staff to support companies in which the municipality has either a full or partial ownership stake. This staff works closely and frequently with the leadership of the state-owned companies (like Metroselskabet), which are often run by political leaders. When political officials on the board have new proposals or questions about projects or major decisions, they are able to request analysis and answers from the technical staff at the municipality.

With the exception of certain holidays, there are few national labor regulations in Denmark. Wages, sick pay, pensions, parental leave, and other labor elements are largely established through collective bargaining agreements between employees and employers at the industry level. Collective agreements among industry associations and trade unions are typically negotiated every three years. Most trade groups involved in Metro construction, like concrete workers and bricklayers, have their own collective agreements at the industry level. There is a strong relationship between Metroselskabet, its contractors, and the various trade unions, and that labor is a stable element of project delivery in the region.

While political officials have sizeable influence and power over publicly-owned companies like Metroselskabet, there does not appear to be a significant politicization of these entities. The close relationship between civil servants and technical experts at the municipalities and political leadership of the Board was cited as playing a large role in keeping political influence away from the decision-making process, and allowing Boards to utilize public sector expertise.

System Overview

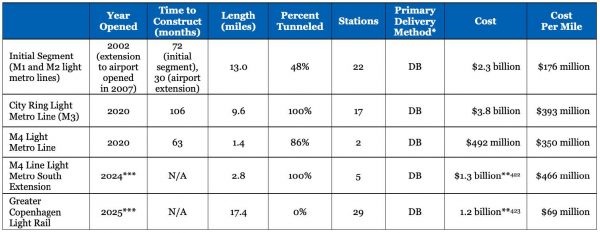

TABLE 13: TRANSIT LINES PROFILED IN THE COPENHAGEN REGION

*A single delivery method is not always used on an entire project.

** Projected costs for unfinished projects

*** Projected opening dates

The M1 and M2 Lines share a common 4.8 mile section through central Copenhagen and include a mix of both tunneled, elevated, and at-grade segments. These lines were delivered using a DB procurement. An international consortium known as Copenhagen Metro Construction Group (COMET) was awarded the contract for civil works and the international firm COWI provided project management and engineering consulting services. Ansaldo STS (Now Hitachi STS) served as the systems contractor, and Rambøll served as the systems consultant. The M1 and M2 lines were the region’s (and the country’s) first major rapid rail transit project, and were built at a cost-per-mile comparable to several U.S. light rail projects despite being tunneled for nearly half of their alignment.

The M3 line of the Copenhagen Metro, known as the City Ring line, runs in a fully-tunneled loop around Central Copenhagen and is one of the large st construction projects ever undertaken in Denmark.424 The City Ring was approved by the Danish Parliament in 2007 and construction sites were set up in 2011, with tunneling beginning in 2013. A joint venture was awarded a contract for civil works and des ign while a separate contract was awarded for architectural finishe s on the stations.425 The project was delayed by nine months and completed $400 milli on over budget.426 Despite this delay and cost ov errun, it was tunneled at a cost significantly less than comparable projects in the United States.

A two-station, 1.4 mile extension of the City Ring line from Østerport to North Harbor was completed in 2020, and branded as the M4 line.427 Metroselskabet is currently building a 2.8 mile, five station extension of the M4 Line from Copenhagen Central Station to serve the South Harbor district. The extension was approved by Parliament in 2015, and is expected to be complete by 2024.428 Once complete, the M4 line will share much of its track with the City Ring Line.

Hovedstadens Letbane is currently building the Greater Copenhagen Light Rail project, a 17.4 mile light rail line expected to be completed in 2025. The light rail line will serve 29 stations in suburban Copenhagen, and interface with the region’s commuter rail (S-Bahn) system. The light rail line will largely run along its own grade-separated track, but share ROW with vehicular traffic in a few segments due to space constraints. This project has also been procured as a DB project, though it is split up into several smaller packages. The LRT is split into eight major contracts: five of which are civil works contracts, representing different sections of the project alignment, and one each for systems and rolling stock.429 Breaking up the contracts in this way was intended to attract more competition and allow for the participation of local and small businesses.

As a relatively new system that was constructed at a cost-per-mile in line with comparable projects in Europe and the United States, albeit with some delays and cost overruns, the Copenhagen Metro offers valuable lessons learned regarding project management and design.

The City Ring line is a particularly useful example to highlight both positive and negative cost and timeline drivers given construction delays and challenges, as well as positive coverage of its engineering methods and architecture. The Greater Copenhagen Light Rail project, though currently under construction, is projected to be completed at a relatively low cost-per-mile relative to both European and U.S. light rail lines.

Standardization, small stations and automated trains can keep project costs down without sacrificing capacity.

The Copenhagen Metro is notable for compact yet spacious stations with ample natural light, and small but frequent automated trains that run at high frequencies to handle rush-hour demand without overdesigning stations. This approach was part of a deliberate desire to avoid over-designing stations to meet peak service, which would leave station space largely underutilized during non-peak hours.

The Metro uses standard, automated trains produced by Hitachi Rail Italy that span a total length of 128 feet and contain just three cars, considerably shorter than trains on other European and U.S. metro systems. The system compensates for the reduced train capacity by running trains as often as every two minutes, which is possible due to the system’s automation. This also enabled stations to be designed with shorter platforms and compact footprints that span just 210 by 65 feet. These cut-and-cover stations fit comfortably within the existing urban fabric of the city, and are often located above existing or new parks and plazas to minimize land acquisition and street disruption.430 They have an average depth of 65 to 98 feet, with the exception of the City Ring station located just outside the entrance of the 18th century Marble Church.431

Using a modular “kit-of-parts” approach, the architects of the Metro also standardized sizes, materials, and components for their stations to minimize costs and allow for easy repairs.432 Architects designed as many parts as possible—including wall cladding, platforms, and screen doors—to be either 18 feet wide or tall, allowing for easy replacement of damaged parts and less expensive maintenance.433 One of the few custom elements of the stations on the new City Ring line are colors and materials of the wall cladding, which are intended to give each station its own unique look while still retaining standard sizes.

Architects were also encouraged to challenge and find new methods to meet fire and safety regulations and streamline designs. Among these solutions are dual-purpose features like skylights that allow natural light onto the platforms while doubling as NFPA 130-compliant ventilation devices in the event of a fire, reducing the need for mechanical ventilation devices or equipment rooms in the stations. This approach cut the number of necessary escape shafts by 30 percent.434 Architects also pushed heavily for the inclusion of platform screen doors, which can not only protect riders from falling onto the tracks but also make it easier to ventilate stations by isolating and sealing off the platform from the tunnels in the event of a fire.

Innovative funding structures can keep costs down, better integrate land use with transportation, and galvanize public and political support to help speed up project delivery.

The Copenhagen Metro is unique in being funded entirely through value capture and the redevelopment of publicly owned lands through state-owned, but privately managed, corporations. During the late 1980s and early 1990s, both the municipality of Copenhagen and Denmark faced a stagnant economy and high unemployment. As part of a major effort to re-invigorate the capital region, the national and local governments partnered to identify ways to boost the city’s tax base, attract new residents, and spur economic development.

A national subcommittee proposed new transportation options and identified value capture as a financing mechanism that did not involve raising taxes. The subcommittee recommended developing a new district anchored by Ørestad, a 0.58 square mile area of undeveloped military training ground in South Copenhagen jointly owned by Denmark and the City of Copenhagen, with a Metro system as its backbone.435 The Metro was intended to not only connect centers and neighborhoods across Central Copenhagen, but also spur new development and increase land values in Ørestad, which would in turn help fund the Metro and other new infrastructure.

In 1991, the concept of developing Ørestad and Metro were presented to the Danish Parliament, which passed the Ørestad Act in 1992.436 This act officially authorized and created the Ørestad Development Corporation and tasked it with selling land and developing Ørestad, as well as building and operating a new mass transit system. The Ørestad Development Corporation took out low-interest, state-backed loans against projected future fare revenue and the sale of publicly owned land, ensuring long-term financial stability over the 40 year-long development of the new region and Metro system.

A significant amount of revenue from recent redevelopment projects carried out by the CPH City & Port Development company have been transferred to Metroselskabet to finance new Metro projects. While the M1 and M2 lines were primarily funded by the redevelopment of Ørestad, the City Ring Line has been largely funded by the redevelopment of Copenhagen’s North Harbor.437 To help generate additional land for this redevelopment project, surplus soil and muck from the metro tunnels are deposited into a concrete structure along the water. Nearly 3.1 million tons of muck from the City Ring tunnels have been used to create new land in the North Harbor. Redevelopment of the North Harbor has generated nearly $15 billion in new value, with $5.8 billion redirected to the Copenhagen Metro ($2 billion of which was dedicated for the construction of the City Ring line).438

Metroselskabet has also reported an annual profit for much of its operational history, and receives most of its revenue from fares, which are used to repay construction loans.439 The ability for Metro to run an operating surplus has largely been attributed to the lack of overhead costs from having a driverless system.

In contrast to the Metro, which is funded through land value capture, the city’s light rail is funded directly by the cities, as it operates on existing ROW through suburbs that are already fully built out. While the national government does not have an ownership stake in the light rail corporation, it is covering 40 percent of the project cost. The municipalities are jointly responsible for 34 percent of construction costs, while the Capital Region will cover the remaining 26 percent.440 The municipalities’ share of construction costs is calculated according to population, the number of stations in each municipality, and projected growth rates.

Like the Metro, the municipalities all share ownership of the light rail project, including all risk, construction costs, and operating expenses. As a result, any cost overruns on the light rail project will be shared amongst the municipalities. By requiring all stakeholders to have a direct stake in the project outcome (and final cost), this governance and financing structure was cited as helping keep all 11 stakeholders focused on the communal benefits of the project and preventing municipalities from attempting to extract as many concessions from the project as possible.

Institutions with appropriate staff and legal authority can deliver projects effectively, but lack of coordination can slow down delivery.

As a publicly-owned, privately managed corporation, Metroselskabet has substantial legal authority to complete major projects, which is codified in law by the passage of construction acts in parliament. Metroselskabet has also developed the in-house capacity needed to deliver projects effectively. Given the wide mandate of the Ørestad Development Corporation, Metroselskabet’s predecessor, to both develop a new region as well as build and operate a new rapid transit system, the corporation had to stand up a team of experts in a short amount of time.441

While the M1 and M2 lines relied heavily on outside consultants, Metroselskabet has since brought a significant amount of work in-house, including project management. This is both a result of Metroselskabet gaining significant project delivery experience (and growing popularity as an employer) from the M1 and M2 line s, but also due to the shortcomings of overreliance on consultants. There was a consensus among interviewees that consultants are very helpful in providing specific, technical expertise but are often not good at making major decisions. This became problematic on the M1 and M2 lines, and was one of the reasons why Metroselskabet opted to build a n internal staff for future projects and instead rely on consultants for specific technical expertise it could not afford to retain in-house.

There is not a major salary disparity between Metroselskabet and the private sector, making it much easier for the company to attract and re tain qualified staff. Additionally, Metroselskabet is able to offer unique and interesting roles for prospective employees that allow them to gain more diverse work experience than they would otherwise gain as private contractors. Many jobs at Metroselskabet also allow technical specialists to gain significant knowledge in their field and become experts, which has also helped attract talented staff. Many of the staff that worked on the City Ring project have transferred to working on the Gre ater Copenhagen Light Rail project. As a result, the light rail corporation has been able to rely almost exclusively on in-house staff with consultants limited to design and technical analysis.

While Metroselskabet has been successful in building out an experienced team, both the M1 and M2 lines as well as the City Ring line experienced schedule delays and were completed over-budget. To minimize disruptions and delays on the M1 and M2 lines, the project team identified a “critical path” of major milestones and potential bottlenecks that had to be receive close attention in order to move the project along.442 One contractor, however, noted that this heavy emphasis led to the project team paying less attention to elements that did not seem to pose an urgent threat to the project timeline or progress, but ended up causing headaches and requiring more time to resolve.443

The M1 and M2 lines were delivered two years later than planned, largely due to issues and delays during the preliminary stages of the project.444 Delays were mostly attributed to slow design review turnarounds from the Metro staff, communication delays given that designers and specialists were stationed across Europe, rather than in Copenhagen, as well as insufficient time allocated for coordinating design documents.445 There were also at least $385 million worth of claims filed by the contractors on the M1 and M2 lines against the project.446 While most of these claims were due to the early delays on the project, others were a result of instances where the contractors’ decisions on architectural appearances and other functional elements of the project conflicted with the specific wants or desires of the project owners.447

To prevent similar conflicts between contractor’s design decisions and Metroselskabet’s preferences, Metroselskabet bid the architectural finishes on the City Ring stations separately from the tunneling and civil works contract. This approach was intended to attract firms with specific expertise in each area, but also allow Metroselskabet to retain more control over station architecture. Metroselskabet eventually migrated the station contract into the larger DB contract, though this approach introduced unnecessary legal complexity, with some feeling it would have been better to manage both contracts separately.

Tunneling beneath a dense, historic, low-lying city is uniquely challenging.

Both the M1 and M2 lines as well as the City Ring experienced s uccesses and challenges tunneling through dense, historic, and geologically sensitive areas within Central Copenhagen. The contract for the M1 and M2 lines explicitly noted that no damage could be done to any of the historic buildings along the alignments. These lines also ran through portions of Central Copenhagen that were incredibly sensitive to groundwater lowering.448

Strict environmental regulations posed further engineering challenges. On the one hand, the project team was required to minimize the use of chemicals underground to prevent contamination of the groundwater supply. On the other hand, contractors were limited in their ability to draw down the water table belo w the city center.449 Contractors cited early environmental assessment and multidisciplinary cooperation between geologists, engineers, and environmental scientists as critical elements for overcoming these geotechnical complexities.450

The City Ring faced similarly complex tunneling conditions given its proximity to much of the city’s historic, Medieval architecture. Prior to the tunneling work on the City Ring line, archaeologists discovered artifacts from the late Viking age underground, including a 16th century shipwreck and city gates dating back 1,000 years.451 The project team further deployed thousands of sensors on buildings and used computer monitors to mitigate potential disruptions due to construction.452 In some cases, nearby buildings had to be lifted by pipes to mitigate disturbances.453 Over 22,000 monitoring stations provided 200,000 readings each day during construction.454

The municipalities granted Metroselskabet’s request and allowed them to carry out construction activities that would surpass normal noise levels during this time. Metroselskabet’s request and the city’s justification stated that the collective noise pollution impact would not be affected by these construction activities and would comply with the noise limits outlined in the EIA report. Once evening construction began, however, an increasing number of noise complaints were filed by residents. Several resident associations filed complaints, arguing that the noise levels generated by evening construction violated the permissible levels in the EIA and construction act.

Eventually, the Nature and Environmental Board of Appeals ordered a stop to evening construction in July 2013. The complaints resulted in a seven-month delay on the project as Metroselskabet, municipalities, and Transportation Ministry negotiated a solution. Eventually, the Construction Act was amended in 2014 to clarify permissible noise levels, detail processes for adjudicating complaints or appeals, and allow residents impacted by the construction to be relocated or receive compensation if they remained (a maximum of $3,200 a month).458 While these complaints and negotiations resulted in a lengthy delay, the amendment and compensation procedures successfully resolved the issue and allowed for construction to resume with minimal disruptions or complaints.

Construction work on the twin-bored tunnels for the City Ring line was divided into southern and northern portions to account for different ground conditions.455 Whereas the southern portion of the City Ring had similar soil conditions to those of the M1 and M2 lines, the northern portion was slated to run through a mix of clay a nd sand, rendering it more liable to settlement of buildings than the southern portion, which involved tunneling through chalk.456 During the geotechnical surveying phase, the anticipated 350 boreholes needed to assess the ground conditions grew to 500 due to scarce information gathered from the original 350 drillings.

Noise complaints during construction of the City Ring line introduced further challenges and resulted in one of the few high-profile instances of major project pushback and work disruption. During the peak of the line’s construction in 2013, Metroselskabet requested extensions to working hours into the evenings, arguing that the additional hours would speed up construction and allow for less overall disruption. The project’s standard working hours were between 7:00 am and 6:00 pm on weekdays.457

The municipalities granted Metroselskabet’s request and allowed them to carry out construction activities that would surpass normal noise levels during this time. Metroselskabet’s request and the city’s justification stated that the collective noise pollution impact would not be affected by these construction activities and would comply with the noise limits outlined in the EIA report. Once evening construction began, however, an increasing number of noise complaints were filed by residents. Several resident associations filed complaints, arguing that the noise levels generated by evening construction violated the permissible levels in the EIA and construction act.

Eventually, the Nature and Environmental Board of Appeals ordered a stop to evening construction in July 2013. The complaints resulted in a seven-month delay on the project as Metroselskabet, municipalities, and Transportation Ministry negotiated a solution. Eventually, the Construction Act was amended in 2014 to clarify permissible noise levels, detail processes for adjudicating complaints or appeals, and allow residents impacted by the construction to be relocated or receive compensation if they remained (a maximum of $3,200 a month).458 While these complaints and negotiations resulted in a lengthy delay, the amendment and compensation procedures successfully resolved the issue and allowed for construction to resume with minimal disruptions or complaints.